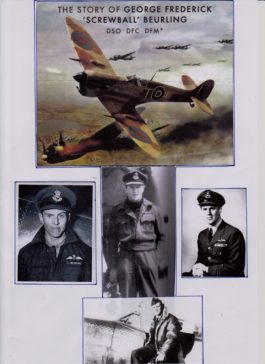

Following on from my developing series of “forgotten” World War II heroes (see “One of the Forgotten Few” – Flt Lt Pat Hughes, DFC – and “The Pilot Who Could Actually See in the Dark” – Flt Lt Richard Stevens, DSO, DFC & Bar), I recently came across the story of Flt Lt George Frederick ‘Screwball’ Beurling, DSO, DFC, DFM & Bar, a truly remarkable, yet untypical, fighter pilot.

George was born in Verdun, Canada, in 1921. His family were honest, working class people who held strong Christian beliefs and brought up their five children accordingly. From a very early age, young George knew exactly what he wanted to do with his life, which was to become an aviator. He began to spend his time, hanging around a local airfield, often to the detriment of his school attendances and, eventually, a bush pilot there took pity and helped him gain some flying experience. By the age of 12, George had ‘handled the controls’ and, with his mentor’s help, built up his hours in the pilot’s seat. There was no easy route to his goal at that time, no Air Force or Government sponsored flying schools, so eventually – to further his aims – he left school and took up full-time employment, in order to afford one flying lesson a week.

When World War II came, Beurling was already an accomplished pilot, but he failed to gain acceptance into the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) because he had not completed his schooling. Undaunted, he worked his passage to Britain on a munitions ship, with a view to enlisting in the Royal Air Force. In wartime, this was a hazardous journey which he had to repeat, because he did not have sufficient paperwork with him, for entry into the RAF, on his initial arrival.

Having finally gained acceptance into the RAF, he was frustrated, at first, by having to begin pilot training from scratch, but he quickly demonstrated his ‘natural’ abilities, both as a pilot and a marksman. Unlike most of his colleagues, he was able to train his eyes to change focus and to pinpoint distant targets with extraordinary speed and accuracy.

Eventually, despite some trials and tribulations, Beurling successfully completed both his training course and the required operational conversion training, which resulted in an initial posting to 403 Squadron, flying Spitfires. His flying record generally matched that of many other contemporaneous pilots and he frequently found himself flying as ‘Tail-end-Charlie’, the most vulnerable position in the entire formation, but it was a role he fulfilled without dissent.

Suddenly, things completely changed for Beurling, when No 403 Squadron became solely RCAF and he was posted away to No 41 Squadron (RAF) where, despite being a seasoned pilot, he again found himself flying at the rear of the formation. This role had nearly cost him his life with 403 Squadron and when he was put in a similar position with his new unit, he was forced to break formation with a crippled Spitfire. Nevertheless, he managed to damage one of his attackers, which he accomplished with only half of his guns working. This action caused Beurling to be accused of leaving the rest of his section exposed, although he insisted he only broke formation because he was under attack and had a damaged Spitfire. His CO evidently agreed, but a second incident followed only three days later, when his CO and the rest of the squadron initially ignored his radioed warnings of an imminent attack (no-one else could see the enemy, only closer friendly aircraft, and his warnings were dismissed). Then, because a late manoeuvre carried out by his CO would have left him as an easy

target, Beurling broke formation and turned defence into attack, destroying one of the enemy and partially breaking up the intended ambush. From this moment, his fate sealed, he was ostracised by most of the Squadron and accused of being a ‘loner’, a label which stuck for the rest of his career. A few weeks later, Beurling learned of an overseas posting and quickly stepped in to take the place of an unwilling pilot.

Beurling was thus posted as a relief pilot to the besieged island of Malta, where he joined No 249 Squadron, flying Spitfire Mk V’s out of Takali airfield. Within weeks, the enemy had turned their full attention on Malta in what was dubbed the ‘July Blitz’. In a matter of a few days, Beurling had claimed his first victory and, in the space of a four month tour of combat operations, he would destroy twenty-seven enemy aircraft, with a further nine damaged. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal and an eventual Bar, before being commissioned (much against his personal will) as a further acknowledgement of his bravery and devotion to duty. A devout Christian, teetotaller and non-smoker, Beurling was never to be found patronising the local bars with his colleagues. Instead, he committed himself to the art of aerial combat and was always ready to pass on the knowledge he had gained to his fellow pilots. Rigidly determined to retain focus, he recognised that it was the men who recklessly indulged themselves who had much briefer and much less effective tours.

As a junior officer, Beurling was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Distinguished Service Order. This latter caused some controversy, as the DSO was considered a medal awarded for leadership and Beurling did not command in the air. However, it was argued that in the same way the great aces of the First World War had led by example, so had Beurling. His CO, ‘Laddie’ Lucas, joined Takali’s flight leader, Wg Cdr Donaldson, in stating that Beurling was tireless in his combat, and always remained very positive in front of his fellow pilots and the ‘erks’. Sqn Ldr Douglas-Hamilton recalled that the young Canadian, ‘was generally smiling and nearly always in what is popularly known as “good form”, a sentiment which was echoed time after time by his contemporaries on Malta.

Yet Beurling had not led a charmed life; during his time fighting out of Malta, his own Spitfire was damaged on several occasions, when he was forced to crash-land or even bail out, and he was wounded twice. Despite his exertions and wounds, Beurling never showed his tiredness or battle fatigue. His extended tour of operations only came to an end due to the concerted efforts of his doctor, his CO and following the personal intervention of the AOC.

If caught in the gun-sight of an enemy aircraft (Malta pilots regularly faced odds of five, ten or twenty to one), Beurling could throw his Spitfire around like no other pilot. One of his tricks was to pull back so hard on the ‘stick’ that his aircraft would stall violently and be thrown over onto its back before entering into a spin – a move no enemy pilot could follow and which few Spitfire pilots dared to emulate. Another method of dropping out of combat like a stone was to simultaneously push both ailerons and the rudder into a turn. Beurling was expert at turning defence into attack and, on one occasion, when faced by four enemy aircraft firing at him in a pincer movement, he deliberately flew into the Macchi Me 202’s rounds rather than take the cannon shells of the Messerschmitt Bf 109’s. His gamble paid off.

Beurling had been accused of being a ‘loner’ while flying with 403 Squadron in UK and it was said that the air battle over Malta better suited his mentality. From this, the idea has grown that he was allowed to just go off and shoot down enemy aircraft at will. This is far from the truth. Over Malta No. 249 Squadron generally flew in pairs, something his flight commander drummed into Beurling on day two. The young Canadian took his leader’s words on board and was never reprimanded for disobeying this rule, nor any other order. He was not guilty of waging a private war, as the island was limited in its 100 octane fuel supply and every sortie had to count. No-one, not even Beurling at the height of his prowess as a fighter ace, had licence to roam freely and shoot down enemy aircraft. When Beurling’s Spitfire suffered radio failure (a valid excuse to act alone) he duly returned to base. If Beurling was scrambled, he followed the Controller’s orders and the same went for air tests, or any other authorised flight; if given a vector, he obeyed orders, otherwise he landed. Moreover, Beurling was a team player and constantly saved the lives of his fellow pilots in combat, on more than one occasion being shot down as a result. His ‘kills’ were largely attained while fighting in a general dogfight, hence they were witnessed by his pals and allowed. Occasionally, Beurling became separated and his ‘kills’ were downgraded to ‘probables’ or ‘damaged’, but that was true of any fighter pilot.

What Beurling did do, which enabled him to steal a march on his colleagues, was to sit in his cockpit awaiting the scramble, keen to get even a few seconds height advantage in a battle climb, by reducing his scramble time. Due to fuel shortages, the Controller was forced to wait until the very last moment before giving the scramble, because he had to be certain that a particular raid was not a feint. It was also vital to use only the minimum number of aircraft to effectively deal with the threat, so as to hold back a reserve in order to tackle the next raid.

Sometimes, Beurling’s extra minutes in the air meant that he and his wingman had the advantage of height over the rest of the formation. He used this to the Squadron’s advantage and would act as spotter or come down on enemy fighters, who were aiming to catch the Spitfire pilots out, by attacking from above and out of the sun. On other occasions, Beurling waited until he spotted the most highly skilled enemy pilot – and dived down to take him on.

When he did go into combat Beurling used his ammunition sparingly, lining up his enemy at close range before pressing the gun-button, often shooting down or badly damaging two, three or even four enemy aircraft in a single sortie. His keen eyesight, steady nerve and mastery of deflection shooting quickly made him Malta’s highest scoring ace; this despite bouts of Malta Dog, a type of dysentery brought on by the siege conditions.

On 14 October 1942, Beurling once again came to the rescue of one of his pals, although this time he was shot down and wounded in the heel. This led to his evacuation to Gibraltar, but still he could not escape the wartime drama when he was one of a handful of tour-expired pilots to survive an air crash.

Having left his homeland as an anonymous deckhand on an ammunition ship, Beurling returned to Canada a national hero and front-page news since the end of July 1942. He was a journalist’s dream and the press hung on his every word. Tall, handsome and dashing, with steely blue eyes and tousled hair, alongside his casual appearance and dislike for authority, his personal traits played into their hands. He stood out from the crowd and the press made much of quotes that Beurling was a ‘loner’, both in the air and on the ground, that he was untidy in his dress and that he could be awkward and an anti-disciplinarian. Beurling was often heard referring to things as being ‘Screwball’ and this stuck as his nickname, although the press at the time preferred to adopt his boyhood nicknames of ‘Buzz’ or ‘Buzzey’. Reluctantly carrying out publicity duties and hating, in particular his role of promoting War Bonds, Beurling was at least able to give lectures to fellow aviators and pass on his experiences and his theories on deflection shooting, with many seasoned combat pilots later giving testimony to the value of his tuition.

It is not surprising that Beurling continued to long for the excitement and adrenalin of combat flying and soon began to show his distaste with the drudgery of mass formation escorts, to which he was subsequently allocated and he was being repeatedly reprimanded for low flying and unauthorised aerobatics. Consequently, having transferred to the RCAF full of enthusiasm, he soon resigned his commission and started to search elsewhere for a combat flying role. In 1948, he found such an assignment in Israel and left Canada for the last time. Tragically, he died in an air accident in Rome when the engine of a transport aircraft he was test flying failed, following maintenance, and he died at the controls. Within a generation, his name had been almost forgotten by all, except those who had served alongside him in Malta. A long term friend of Beurling wrote shortly after his death, ‘He wanted to be the best fighter pilot in the world. He never gave much thought to becoming the oldest fighter pilot in the world.

Ben Croucher

-4-

« RAF Hereford Main Gates (And More) – Dave Williams (324th) || 60 Years Gone In A Flash – John Dyer (46th) »