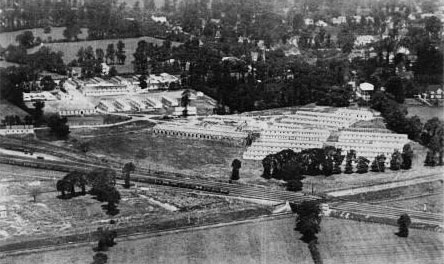

In 1921, a trial scheme for apprentice clerks began with 36 young men being enlisted as Boy Clerks (but known as The Experimentals) at RAF Record Office Ruislip. Their performance and results proved that the scheme was worth continuing and following further discussions the Treasury agreed to the scheme which provided 2 years apprentice training as junior clerks and messengers. Training started at Ruislip in October 1925. IInitially all apprentice clerks were trained as Clerks General Duties, but after the 61st Entry in 1927, a third of each subsequent Entry were trained in stores procedures. This Scheme continued until 1942 and the passing out of the 61st Entry, with, appropriately, the Inspecting Officer being Air Vice-Marshal Sir John W Cordingley, KCVO, KCB, CBE. Between 1925 and 1942, 2,080 apprentices were attested at Ruislip, with service numbers in the block 590001 – 592080. They apparently revelled in their soubriquet of ‘John Willie’s Boys’; however, here the ‘Boys’ were showing their independence – since their Commanding Officer’s Christian names were ‘John Walter’! The 2080 apprentices were trained in accounting and general clerical duties, whilst four evenings a week they were trained in shorthand and typing. Durinmg the day, the apprentices acted amongst other duties, as messengers within the RAf Record Office, earning one shilling a day (5p) in their first year and one shilling and sixpence (7.5p) in their second year. 61 Entries trained at Ruislip with the last entry enlisting on 28 April 1941. Of those trained at Ruislip 819 were commissioned, 4 of which reached Air Rank. Over 1000 men reached SNCO rank. Of the remainder, 455 became aircrew. Memories of the vital role that RAF Ruislip played in the organisation of the RAF were rekindled in June 2000 – the 75th anniversary of the formation of the RAF Apprentice Clerks – when a memorial plaque was installed on the former Main Guardroom wall at Ruislip.

I had been sent a railway warrant and instructions to catch a train from Marylebone station for Ruislip. Living as far away as the Midlands, and never having travelled so far, it was as well that the instructions were fairly complete. The Underground was quite new to me and an adventure in itself. Although I entered it with sometrepidation, I was surprised how easy it all was – so easy, in fact, that thenceforth I never used any other form of transport through London.

We were met, a Ruislip station, on this cold January afternoon and taken to the camp where we were greeted by curious members of earlier entries – some to adviseus to “Get some in” (whatever that meant) and some to invite us to lend them money until Friday. I think I managed to avoid that trap though I could have been carrying as much as a pound in my pocket – perhaps I had been warned.

We would then, have been shown to our barrack room. I was quite impressed with it. Everything was clean and tidy and the bed was already made and looked comfortable. Then we went to tea and I could find no fault with that. Drinking tea out of a pint mug with no table cloth seemed strange, but I supposed I could get usedto it. The meal was fried bacon and sausages with baked beans. Baked beans I had never tasted before and I thought them delicious. I was too much of a rooky (though I did not yet know the word) to realise that I was already making my first mistake – you must always find fault with your food if only to show that you were used to something better. Later you would find that at each meal there was the Orderly Officer to whom you could address any complaint, but that would have been taking things too far. In fact during my whole time as an apprentice I don’t recall anyone having the courage to complain. What a hero you could have been! Something like Oliver Twist, but where did it get him?

The next day was taken up with enlistment formalities.It was explained to us that we would serve for twelve years during which, if we were clever enough we might expect to reach the rank of Sergeant. At the end of our engagement we would receive a gratuity of £100, a mouth-watering thought but an eternity ahead. Then, some time in the evening I think it was, we were attested. It was very solemnly explained to us that we were about to take the oath and that, if we had any misgivings, now was the time to express them. I could not have imagined than anyone would draw back so close to the brink. But I was wrong; one of our number shuffled forward and said that he would like to change his mind. He was duly given an orange, a bag of sandwiches and a railway warrant home.

We returned to our barrack room to find everything spick and span and our beds nicely made. I for one had no doubts about having done a wise thing and looked forward to getting kitted out with my uniform. I could hardly wait. Next day they brought up the subject of pay. We knew of course that we would be paid a shilling a day but it was explained to us that we would only actually receive three shillings a week. The remaining four shillings would be saved for us until we went on leave so that we could “paint the town red”. It was pointed out to us that even three shillings was a lot of money for a young lad to be carrying around and that we could, if we wished draw only two shillings – and thereby, I presume, paint the town even redder. Not many took up this kind offer but at least some did. From then on things quickly went downhill. We had not questioned the magic by which our room became tidy or who had made our beds so neatly. It’s a thing you take for granted but it suddenly stopped. We found that not only were we expected to make our own beds, but that the beds themselves were something special – they were McDonalds! To the uninitiated, which we certainly were, this means that the bedstead, which was unencumbered with springs, was in two parts and so could be retracted to half its length. And in daytime retracted it had to be, which meant, if you think about it, that the bed had to be made, not once, but twice each day. Except Sundays, that is, when you could and did wallow in your squalor.

The first items of kit we received must have been our pint china mug, and knife, fork and spoon, or irons as we learnt to call them. Life seemed to revolve around them, particularly the mug. As a broken mug cost, I think, sixpence to replace, some unscrupulous people felt it made better economic sense to help themselves from someone who had been more fortunate. Sadly this lad, who would normally not dream of such a thing, might feel obliged to join in the game. And so it went on like musical chairs. The music stopped just before the next kit inspection when the last unfortunate in the chain forked out his reluctant sixpence. There were now a few regulations to learn. We were told that the RAF having assumed responsibility to our parents for our moral welfare, it would be an offence if at any time we “associated with females” We were allowed to leave camp but were required to book out at the guardroom. There we would be inspected, and if our appearance was not up to scratch, instructed to return to our barracks. To discourage us from breaking rule one, apprentices were not permitted to book out separately and, when they booked in they must be with the person with whom they left. Furthermore all places more than three miles from the camp gates were out of bounds. Love, they say, will find a way, but at Ruislip I don’t think that it did too often. In fact these rules were probably quite unnecessary – most of us would have runa mile if a girl had looked at us! They did however have the effect that anyone without friends was, to all intents and purposes, permanently confined to camp. Incidentally the times for returning to camp were also strictly regulated. I forget exactly what they were, but I think we had to be back by 2130, except that on occasions a late pass to 2230 was allowed. Then of course there was smoking. In a way Ruislip may have been ahead of their time by banning it in days when most people saw it as a fairly harmless vice.Admittedly when you reached the age of eighteen you could apply for a “Smoking Pass”. This authorised you to smoke when off duty and outside all buildings. How times have changed – today you are entitled to the vote at that age! Unfortunately the regulation probably had the opposite effect to that intended. Few smokers get enjoyment out of cigarettes when they start and I am sure many of us would not have persevered if the habit had been legal. Whether or not this is true, it was here that I became hooked for most of my time in the service.

Sometime during our first week we were introduced to “Domestic Evening”, or, as the old hands soon taught us to call it, “bullshit night”. It was very largely about polishing lino and came as something of a shock. If I had thought about it at all, it had not occurred to me what hard and it is.There was always plenty of polish to be had but not enough bumpers to spread it. Trying to slide on a floor made sticky with too much polish with each foot on a square of old blanket material was soul destroying. Give me Bluebelling the windows or Vimming the washbasins any day! We quickly learned that polishing lino became less of a chore if it had been looked after for the rest of the week. Consequently no-one actually walked on the floor at all but all slid silently and mysteriously between the outside door and bedspace.Another routine we quickly learned was to do with laundry. We were entitled to free laundry to a value of ninepence a week. For that we bundled up one shirt, two collars, one vest, one pair of pants, a pair of socks and I think a pair of pyjamas though I’m not sure about the last. One could send more but, as you would have to pay for the extra, no-one did. We were also entitled a clean pair of sheets each week, though strangely this was a privilege for us which would be withdrawn when we became airmen. You did not wear civilian clothes at all. Those you arrived in were stored away at the end of the billet.

“Lights out” was, I think, at ten o’clock and talking after that time was forbidden. You were permitted to keep a radio in the billet, if you had such a luxury, but only aftersubmitting an application. You would then be required to make a fixed payment for the electricity consumed!

I won’t say too much about the trade training we received. As I remember there was not all that much, considering that it was the only reason for our being there. I should mention however the touch typing training we did, Accounts and GD clerks alike, on the dreadful Oliver typewriter. Once you had mastered it, with its awful nonstandard three-bank keyboard you would have the utmost difficulty adapting to any other.

On second thoughts something of our accounts training also comes to mind. I think it came under the heading of “Mathematics” but consisted of what was called “Long tots and cross tots”. You were given a book on each page of which was a table of perhaps six columns by about twenty rows of pounds, shillings and pence. The instructor would tell us that, when we had got them to balance, we could leave. Some people were leaving before I had got to the end of the third row and by the time I had achieved a balance I was on my own. In some ways I preferred polishing lino – perhaps I was more cut out for it!

By the time the war started we were well into the routine and although I moaned with the rest, as I was expected to, I really enjoyed life. We were no longer the junior entry, and had jeered at the next to arrive. Although we would not admit it, we enjoyed our drill, particularly when we started rifle drill. We were, I think, reasonably well behaved and our billet was spotless. Then into this serene situation descended the “E” Class reserve. Some short time previously the Air Ministry had hit upon the idea of offering retired airmen, who had completed their reserve commitment, the opportunity for a further period on the Reserve. Not too much effort was required and it seemed fairly well rewarded. Forgetting the old service principle “Don’t volunteer for anything”, these poor innocents took the bait. The ink had hardly dried on their signatures when these old men, which is what to us they seemed, were dragged from the bosom of their families and placed in the barrack room opposite. We were appalled. Having been trained to expect to be treated like POWs we were amazed at what they got away with. Their room was scruffy and they seemed to return from town at all hours carrying beer in their respirator haversacks. Perhaps our superiors realised the bad effect their example was on us because the next thing was that we were all moved into the gymnasium. What sticks in the memory about that is that we slept on the floor and that because of the risk of air raids the only light was one feeble blue painted bulb.

About the only other thing I remember about the how the war affected us is that we were all sent to work in an immense typing pool in No 4 MU at Ickenham. We travelled each day to a large draughty hangar, to sit in rows typing stencils for P.O.R.s. It seems that before the war each unit published what were known as “casualty forms” and sent copies to, amongst other places, Record Office. With the outbreak of the war, smaller units were unable to do this and so the system was changed and a manuscript was send to Record Office from which we produced the duplicated copies. It was here that I learned about the magic scarlet correcting fluid for use on stencils. I would never have completed one without it.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about our apprentice training is that no mention ever seems to have been made about flying or even aeroplanes. I presume that we all must have had some interest in aircraft or we would not have joined the RAF. One would have expected that they would have thought it desirable to encourage and foster that interest but, during the whole of my time at Ruislip, I was never shown an aircraft even though there was an airfield only just up the road at Northolt. Some of us did visit an air display there once but only as members of the public. The image of a Hawker Fury being held down after take-of, and then climbing vertically, still sticks in my mind. But we never actually got near to an aircraft. I don’t think anyone resented it; we didn’t expect any different. We were there to learn what happened to the various coloured copies of forms 674 and about Crockery and Glass Breakage Allowance or to go on errands in Dead Files hunting for missing documents which no-one really expected us to find.

Our entertainments were very simple. A weekly visit to the pictures cost sixpence. There was wrestling in the barrack-room and, I am afraid, teasing those unlikely to hit back. And, after the war had started, there was modifying our ceremonial hats to try to make them look like the German ones we had seen at the pictures, and which we so much admired; here a fine balance had to be drawn between what we thought looked dashing and the opinion of an inspecting officer or even Corporal Keating!

Still – I wouldn’t have missed it. Well only some of it!

The son of a Yorkshire miner George Unwin was born on January 18th 1913 at Bolton-on-Dearne.He was educated at the local grammar school, where he was a Fine footballer (he later turned out for the .RAF).Determined not to join his father in the mines, he answered an advertisement offering apprenticeships in the RAF; he joined as a boy clerk when he was 16 and trained at Ruislip.

After serving at Uxbridge for four years Unwin was selected for pilot training in 1935 and the following year he joined No 19,Sqn flying the bi-plane Gauntlet fighter, He served with the squadron for four years, and was one of the very few to fly in action throughout the Battle of Britain and survive unscathed.In August l938 Unwin was a sergeant pilot serving on No 19 Squadron when it became the first to receive the Spitfire. He was one of the original RAF pilots to fly the new fighter and, in the early days, he flew regularly as Douglas Bader’s wingman.

No 19 was heavily engaged during the Dunkirk crisis in May 1940. Although an experienced pilot by then, Unwin was not allocated an aircraft for the first sortie, He complained bitterly, and it was this that earned him his nickname, which remained with him for the rest of his life. He was in action the next day, however and soon registered his first success. The squadron was in the thick of the intense fighting and, by the end of the evacuation he had claimed the destruction of five enemy aircraft, two of them unconfirmed.

Unwin flew throughout the Battle of Britain, mainly from Duxford. On August 16 his section of four aircraft attacked a large formation of fighters escorting bombers, and he shot down one fighter over Clacton.Early.

September saw the introduction of the controversial “Big Wing” employing three squadrons, including No 19, The wing flew its first offensive patrol on September 7. After attacking a fighter, Unwin became detached from the rest of his formation. Finding himself alone, he saw Hurricanes engaging a big formation of bombers and went to assist them. A large force of Messerschmitt Bf 109s immediately attacked him over Ramsgate, and he turned to engage them. He hit at least five and two were confirmed as destroyed.

On September 15, the height of the battle, Unwin and his section attacked a force of 30 Bf 109 fighters escorting a large formation of enemy bombers; he dived on one and shot it down over London before climbing back to height, where he found two others flying alone. He shot down both. Two days later he was awarded an immediate DFM for “‘his great courage in shooting down 10 enemy aircraft.

Over the next few weeks Unwin accounted for three more German fighters and he shared in the destruction of two others. He achieved his final success on November28 when he was patrolling over a convoy. Early in December it was announced that Unwin had been awarded a Bar to his DFM.In December 1940 he was rested and by then had become one of the most successful fighter pilots of the Battle of Britain. He was also one of only 60 men who received a double DFM in the Second World War.

Initially Unwin would not apply for a commission, since a senior flight sergeant earned a few more shillings than a junior officer. Once the rules were changed he relented and was interviewed a number of times; but his background and passion for football did not impress the selection boards. A colleague tipped him off that an interest in horses would make a good impression. For his next interview he decided to tell the panel of his knowledge and love of horses. The board accordingly recommended him for a commission – he had omitted to tell them that his experience was limited to the occasional meeting with the pit ponies at his father’s coalmine. He was made a pilot officer in July 1941,Unwin became a flying instructor, first at Cranwell and then at Montrose where he remained until October 1943. He then converted to the Mosquito before joining No 613 Squadron in April 1944; he was based at Lasham and employed on night intruder Operations. As D-Day dawned, No 613 roamed behind enemy lines attacking fuel supplies, airfields and road and rail links.

By October Unwin had flown more than 50 intruder operations, and he was sent to the Central Gunnery School as an instructor remaining until June 1946. With the resurrection of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force, he joined No 608 (North Riding) Squadron as one of the regular RAF pilots training the squadron’s weekend flyers.

Unwin was given command of No 84 Squadron in August 1949, flying the Brigand aircraft from RAF Habbaniya in Iraq. Within months No 84 was transferred toSingapore to provide ground support during the Malaya emergency.

The Brigand was not a popular aircraft, and the squadron suffered a number of losses. Unwin spotted that some were due to premature explosions in the Aden gun carried under the fuel tanks of the aircraft. He was critical of the Brigand’s performance and was always prepared to display its weaknesses to higher authorities. Nevertheless, he led the squadron on more than 180 rocket and dive-bombing attacks against terrorist positions.Not many commanding officers played football, but Unwin was a regular member of the squadron team until he broke a leg. He was invalided home and given a ground appointment as a wing commander. Shortly afterwards it was announced that he had been awarded the DSO, one of very few awarded to the RAF for operations during the Malayan campaign.

In 1955 Unwin returned to Singapore in charge of administration at RAF Tengah, where he still found time to fly the station’s jet fighters. Three years later he returned to England to become the Permanent President of Courts MartiaL He once commented “I presided over 300 courts martial, and not one chap was found guilty of low flying,” He retired from the RAF in 1961.

In retirement Unwin was the Controller of Spastics Appeals for the southern counties, but he never considered that to be work. A passionate golfer with a handicap of six he lived within walking distance of the Ferdown Club, in Dorset, where he served for many years on numerous committees.In earlier days he played seven days a week, once commenting: “I cut it down to five times in winter.” He continued playing until he was 90 but visited the club two or three times a week until his death.

Small in stature Unwin displayed all the characteristics for which Yorkshire men are renowned: he was pugnacious, blunt, unafraid to speak out, and he had no time for wasters or for the unprofessional. One of his pilots said of him “He was like a terrier, and an outstanding CO who always led from the front. He never failed to back you up if you were right.'”George Unwin died on 28th June 2006 aged 93.

An Interesting Contact

4 Aug 2010

A warm welcome also to another new member Ed Hemmings (8th Entry) who now lives in Canada. Ed has sent me the following information concerning his brother, an ex-Ruislip Apprentice Clerk:

‘I thought I would mention my brother, I.G.S Hemming, who joined the RAF as an Equipment Apprentice in either 1926, 1927, or 1928. He spent his career in the RAF, achieving the rank of Air Commodore and being awarded an OBE. He died in 2003 at the age of 92. I am sorry I don’t know what entry he was in or his service number. It was his success in the RAF which encouraged me to join as an apprentice in 1949.

Administrator Note: Idris Hemmings (590971) CB, OBE enlisted 28th July 1928 and was subsequently commissioned from the rank of Sergeant. Retired as Air Cdre Supply Branch 2nd April 1968.

These remarkable pictures featuring 590177 Frank Williams (12th Entry RAF Ruislip) with friends and family were sent to me in June 2011 by his son Tony who was 81st Entry RAF Halton. Tony also has Frank’s diary detailing his time as an Apprentice Clerk as well as his father’s service record. I am in contact with Tony with a view to obtaining copies of these documents. Frank Williams served for 36 years in the RAF and retired as Squadron Leader S Ad O at RAF Farborough.My sincere thanks to Tony for providing this fascinating insight into Apprentice Clerk life at RAF Ruislip in the 1920s

Do You Have Any Photos Taken During Your Time At RAF Ruislip? If So We Would Be Pleased To Hear From You administrator@rafadappassn.org

administrator@rafadappassn.org

administrator@rafadappassn.org Obituary To Kenneth ‘Ken’ Barker – 591313 (49th Ruislip)

Obituary To Kenneth ‘Ken’ Barker – 591313 (49th Ruislip)